Jewish and Muslim Students Can Work Together Against Prejudice

There are more than 110,000 Jewish and Muslim students in Britain, but it’s not often their shared experiences are considered. Globally, Muslim-Jewish relations are a touchy topic, with the focus on political divisions (such as Palestine-Israel), and an assumption of historical enmity. I have felt this cold, polarising air from both communities, whose leaders seem unwilling to address it.

But born and raised in Alwoodley, Leeds, I grew up with more Jewish than Muslim friends, and realised our startling similarities. The National Jewish Student Survey in 2011 showed the day-to-day issues facing Jewish students. In the main these concerned passing exams and finding a job, but Judaism also played a strong role in encouraging them to support and give to ethical causes. Two out of five had experienced an antisemitic incident in the last year, although just 4% were “very worried” about antisemitism at university.

The Greater London Authority research into the experiences of Muslim students in 2009 suggested a similar experience, both of Islamophobia and of getting the best out of life on campus. Muslim students are engaging in social activism and are concerned about welfare needs, but have the same day-to-day concerns as other students. In summary, young Muslims and Jews want to enjoy their university years, get good jobs and make a difference.

But in 2012, there are troubled waters ahead. Internationally there is thethreat of a war with Iran, which could stoke inter-community tensions – and antisemitism and Islamophobia have not gone away. January saw a vile Nazi-themed drinking game, on a ski trip organised by the LSE athletics union, which was rightly condemned. Also at LSE there was the Islamophobic harassment of a Muslim student after religious sensitivities were provoked by the Atheist Secular and Humanist Society and in Stoke – a place where Muslim students have been harassed by the BNP – an ex-soldier, Simon Beech, was recently convicted of setting fire to a mosque.

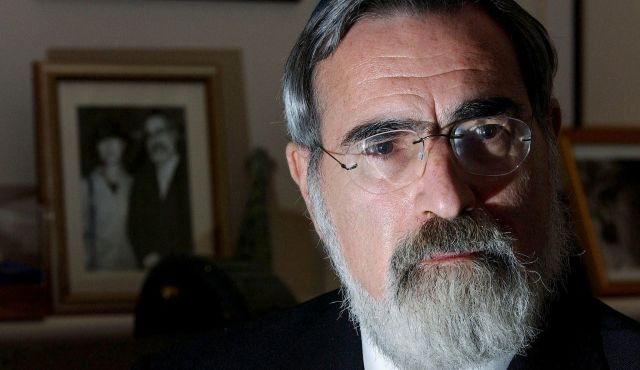

The very existence of Holocaust denial in Britain beggars belief (Mehdi Hasan wrote decisively recently about his shame of some Muslim attitudes) and I have challenged first-hand a tiny minority of people from different backgrounds who think antisemitism “is not real” and casually speak of Jewish conspiracy theories. The chief rabbi, Jonathan Sacks, was right to question, ahead of Holocaust Memorial Day this year, if humanity had learned its lesson.

Wise leadership with sincerity and courage is needed and although there is no simple solution there are three actions I believe are necessary.

The first is education. More religious leaders from both sides should be clear that our scriptural sources decry antisemitism and Islamophobia, and practise the love found in both traditions. We must remember the co-operation of the “Golden Age”, which lasted 1,000 years, and which saw Muslims, Jews and Christians building a civilisation together which laid the basis for the science we know today. This period produced figures including the Muslim Averroes whose ideas, via Thomas Aquinas, found currency in Christian theology – and the Jewish Maimonides, a revered polymath and eventual physician for Saladin the Magnificent, who ushered in a period of peace and prosperity for adherents of all faiths in the Holy Land.

The second is that students have an important role in creating a new relationship which emphasises listening, fights simplistic stereotypes and focuses on our similarities. Students should rise above ugly debates and not lash out at each other, by discussing issues maturely. This is why we support the NUS’s Project on Hate Speech.

A Palestinian student street theatre was attacked at LSE by pro-Israel protesters this week. Campaigning on Palestine and Israel on campus must continue but should respect the right to free expression – and it should target issues, never people. And campaigning against Israel should not be equated with antisemitism.

Finally, the government should not divide young Muslims and Jews. Nick Clegg’s comments attacking the Federation of Student Islamic Societies at a Jewish community event, in Manchester in November, were unhelpful. Similarly David Cameron was right to condemn antisemitism, but wrong to refuse to back his Conservative co-chairman Lady Warsi, who courageously reflected that anti-Muslim prejudice had “passed the dinner table test”. Worryingly, recent research titled Cold War on British Muslims exposed how two neoconservative thinktanks which have advised the Tory party were responsible for fuelling anti-Muslim hatred.

Reconciliation is a road paved with love, respect and forgiveness. I am sure to be criticised from all angles – perhaps for somehow attacking Zionists, or perhaps for being hateful on my “own people” – but we must break free of the prejudices that have plagued us for too long. Last year we commemorated how Albanian Muslims during the Holocaust protected their Jewish brothers and sisters against the Nazis. This is a moving story, but we should not see it through the prism of Muslims and Jews, but as a story of human beings who were opposed to injustice. Many students on the ground are working for good – our civic and political leadership must have the courage to do the same.