NY Rabbi Brings Style to Interfaith Activism

December 10, 2009

Adam Phillips | New York

Influential New York rabbi hosts a weekly talk show on an American Muslim TV network to encourage religious inclusiveness, tolerance

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield is president of CLAL, a New York-based non-profit organization dedicated to the promotion of Jewish knowledge and religious tolerance around the world. Hirschfield is also author of You Don’t Have to Be Wrong for Me to be Right and the host of a popular interfaith program on a leading Muslim television network.

From the modern art on his walls to the traditional Talmudic texts stacked on the shelves, the décor of CLAL’s midtown offices reflects Rabbi Brad Hirschfield’s eclectic style and his unique mission. Dressed in a dark, conservative suit, yet sporting a shoulder-length salt-and-pepper ponytail, Hirschfield says his organization takes its name from the Hebrew word for inclusive. “And that really summarizes the work that we do here,” he says.

Inclusiveness through respect of other religious views

“We believe there should be a place in Jewish life for everyone who wants one, regardless of dogma or doctrine or belief,” Hirschfield says. “It doesn’t mean that everyone is going to agree. Inclusiveness is not about the watering down of all difference, or the flattening of all distinction. It’s about an expansiveness of sprit.”

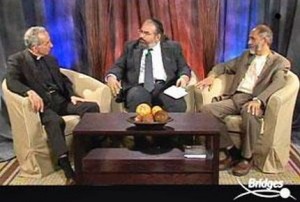

Rabbi Hirschfield is the host and creator of a popular series on the American Muslim Television Network called Building Bridges. On the program, he and clergy from the Muslim and Christian faiths discuss the issues of the day, such as abortion and immigration policy. He says the purpose of the show is to spotlight what he terms the authentic inter-religious encounter, not the kind of ‘feel good’ interfaith dialog where differences are glossed over or ignored.

“We can really disagree but model for people a kind of disagreement that doesn’t turn ugly,” Hirschfield explains. “Being in the presence of those with whom you disagree neither dilutes your faith nor dishonors the God in whom you believe. In a world where people are blowing each other up in the name of God… we’re going to have to figure out an ethic which knows how to be with each other when there is genuine difference.”

Raised by secular parents

Hirschfield was born in 1963 and raised in a Chicago suburb. Although his parents were secular, they sent him to a religious school, and he credits them with teaching him respect for others. When he was just 12 years old, Hirschfield asked his mother to buy kosher meat for him, and to use ritually pure plates in keeping with Jewish dietary laws. She refused, yet promised to make the entire home kosher because, in her words, “in your own home, you don’t eat on different plates.” But she also told her son that he would have to respect the fact that other members of their Jewish family were not traditionally observant.

Hirschfield says he learned two key lessons from this.

“The first was that she would not allow her fear of my new-found expression of faith to drive a wedge between us. And the second one was I wasn’t going to find my newfound faith to use as a club to beat up on them, like suddenly I was a better Jew, or a better human being.” And Hirschfield adds, “When people can figure out how to follow those two rules, the world is going to be a lot safer and people will have the freedom to be as deeply and passionately religious as they choose to be.”

Life among Zionists

Hirschfield himself is no stranger to passionate – and partisan – religious fervor. In 1981, when he was 17, he joined a settlement of religious Zionists outside the West Bank City of Hebron. He often carried a Bible in one hand and a gun in the other. But, one day he learned that fellow settlers had just killed two innocent Palestinian school children in a reprisal raid. In shock, he went to a settlement leader and said something was terribly wrong. He remembers the man agreed it was sad that innocent children had to die.

“But he said ‘there is no fundamental problem with our aspirations or our way of getting there’ and ‘now is not the time to ask questions,'” Hirschfield recalls. “And it was those two comments that made me realize, I don’t think this is salvageable. Because the more important the issue, the more important it is to raise questions.”

Embracing openess

Hirschfield returned to America, where he met Irving Greenburg, the Orthodox rabbi who founded CLAL. He was deeply moved by the elder man’s commitment to Jewish values, while embracing a spirit of curiosity and openness to others. Hirschfield went to work for him, and became an Orthodox rabbi himself. His book, You Don’t Have to Be Wrong for Me to Be Right, is Hirschfield’s attempt to share the pluralist attitude he views as essential to a healthy and sustainable spiritual life.

In the book, Hirschfield cites the Bible story where God drowns the Egyptian army as it pursued the Israelites who had just escaped from slavery. According to rabbinical legend, when the angels began to sing in celebration that the Egyptians were dead, God silenced them saying how dare you sing when my creatures are perishing?’ The message is that, just as one can view one’s oppressors as evildoers and as children of God, rather than good OR evil, one can see competing truths as equally valid.

For many people, Hirschfield explains, that’s a difficult concept.

“Most of us, especially in the West, are essentially trained in what we call a kind of classical philosophical mindset in which truth will always be the product of falsifying everything else. Like peeling an onion get the last shred of onion and that’s ‘the real onion!’ That’s a very dangerous way to think about life because it basically says that everything that isn’t exactly as you think it ought to be has to be gotten rid of.”

Hirschfield adds that Judaism offers some useful wisdom on truth-seeking. “When the rabbis came along and began to think about truth,” he says, “it wasn’t that kind of stripping away. It was an additive process. ‘Oh. You say this. I want to add another thing.’ And a third guy comes and says ‘I want to add my idea!’ And truth becomes, as opposed to peeling an onion, the linking of links in a chain.”

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield was selected to be a plenary speaker at the Parliament of the World’s Religions, held December 4-9 in Melbourne, Australia — a quadrennial event Hirschfield calls “a festival of faith.”